Introduction

- The following page discusses how to use R’s

polrpackage to perform an ordinal logistic regression. - For a more mathematical treatment of the interpretation of results refer to: How do I interpret the coefficients in an ordinal logistic regression in R?

Preparation

Make sure that you can load the following packages before trying to run the examples on this page. If you do not have

a package installed, run: install.packages("packagename"), or if you see the version is out of date, run: update.packages().

require(foreign) require(ggplot2) require(MASS) require(Hmisc) require(reshape2)

Version info: Code for this page was tested in R version 3.1.1 (2014-07-10)

On: 2014-08-21

With: reshape2 1.4; Hmisc 3.14-4; Formula 1.1-2; survival 2.37-7; lattice 0.20-29; MASS 7.3-33; ggplot2 1.0.0; foreign 0.8-61; knitr 1.6

Please note: The purpose of this page is to show how to use various data analysis commands. It does not cover all aspects of the research process which researchers are expected to do. In particular, it does not cover data cleaning and checking, verification of assumptions, model diagnostics or potential follow-up analyses.

Examples of ordinal logistic regression

Example 1: A marketing research firm wants to investigate what factors influence the size of soda (small, medium, large or extra large) that people order at a fast-food chain. These factors may include what type of sandwich is ordered (burger or chicken), whether or not fries are also ordered, and age of the consumer. While the outcome variable, size of soda, is obviously ordered, the difference between the various sizes is not consistent. The difference between small and medium is 10 ounces, between medium and large 8, and between large and extra large 12.

Example 2: A researcher is interested in what factors influence medaling in Olympic swimming. Relevant predictors include at training hours, diet, age, and popularity of swimming in the athlete’s home country. The researcher believes that the distance between gold and silver is larger than the distance between silver and bronze.

Example 3: A study looks at factors that influence the decision of whether to apply to graduate school. College juniors are asked if they are unlikely, somewhat likely, or very likely to apply to graduate school. Hence, our outcome variable has three categories. Data on parental educational status, whether the undergraduate institution is public or private, and current GPA is also collected. The researchers have reason to believe that the “distances” between these three points are not equal. For example, the “distance” between “unlikely” and “somewhat likely” may be shorter than the distance between “somewhat likely” and “very likely”.

Description of the Data

For our data analysis below, we are going to expand on Example 3 about applying to graduate school. We have simulated some data for this example and it can be obtained from our website:

dat <- read.dta("https://stats.idre.ucla.edu/stat/data/ologit.dta") head(dat)

## apply pared public gpa ## 1 very likely 0 0 3.26 ## 2 somewhat likely 1 0 3.21 ## 3 unlikely 1 1 3.94 ## 4 somewhat likely 0 0 2.81 ## 5 somewhat likely 0 0 2.53 ## 6 unlikely 0 1 2.59

This hypothetical data set has a three level variable called

apply, with levels “unlikely”, “somewhat likely”, and “very likely”, coded 1, 2, and 3, respectively, that we will use as our outcome variable.

We also have three variables that we will use as predictors: pared,

which is a 0/1 variable indicating whether at least one parent has a graduate degree;

public, which is a 0/1 variable where 1 indicates that the

undergraduate institution is public and 0 private, and

gpa, which is the student’s grade point average.

Let’s start with the descriptive statistics of these variables.

## one at a time, table apply, pared, and public lapply(dat[, c("apply", "pared", "public")], table)

## $apply ## ## unlikely somewhat likely very likely ## 220 140 40 ## ## $pared ## ## 0 1 ## 337 63 ## ## $public ## ## 0 1 ## 343 57

## three way cross tabs (xtabs) and flatten the table ftable(xtabs(~ public + apply + pared, data = dat))

## pared 0 1 ## public apply ## 0 unlikely 175 14 ## somewhat likely 98 26 ## very likely 20 10 ## 1 unlikely 25 6 ## somewhat likely 12 4 ## very likely 7 3

summary(dat$gpa)

## Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max. ## 1.90 2.72 2.99 3.00 3.27 4.00

sd(dat$gpa)

## [1] 0.3979

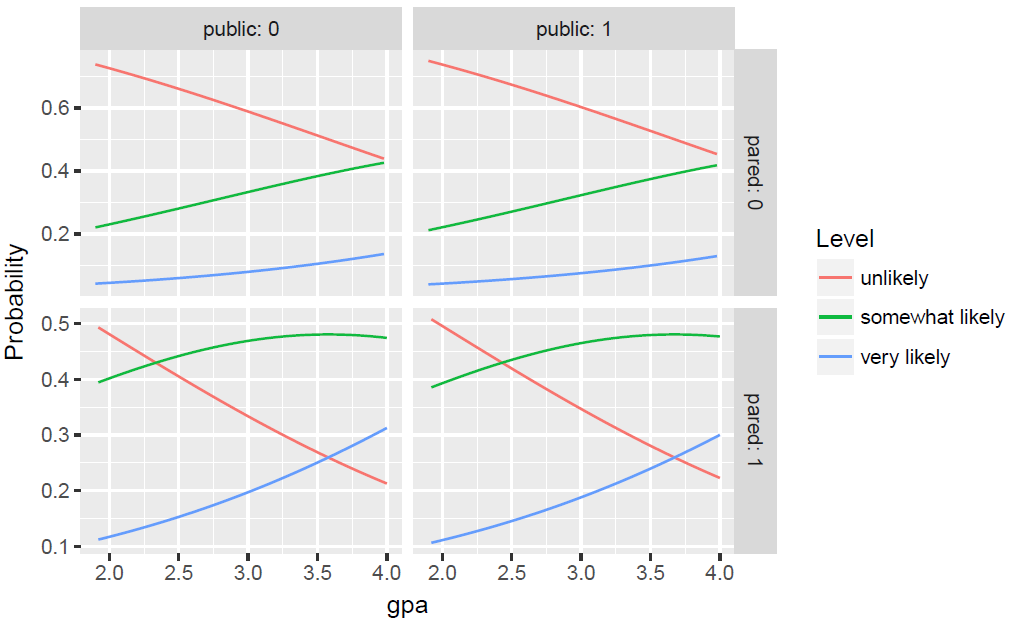

We can also examine the distribution of gpa at every level of applyand broken down by public and pared. This creates a 2 x 2 grid

with a boxplot of gpa for every level of apply, for particular values of paredand public. To better see the data, we also add the raw data points on top of the box plots, with a small amount of noise (often called “jitter”) and 50% transparency so they do not overwhelm the boxplots. Finally, in addition to the cells, we plot all of the marginal relationships. The margins make the final plot a 3 x 3 grid. In the

lower right hand corner, is the overall relationship between apply and gpa which appears slightly positive. To do this, we use the ggplot2 package.

ggplot(dat, aes(x = apply, y = gpa)) + geom_boxplot(size = .75) + geom_jitter(alpha = .5) + facet_grid(pared ~ public, margins = TRUE) + theme(axis.text.x = element_text(angle = 45, hjust = 1, vjust = 1))

Analysis methods you might consider

Below is a list of some analysis methods you may have encountered. Some of the methods listed are quite reasonable while others have either fallen out of favor or have limitations.

- Ordered logistic regression: the focus of this page.

- OLS regression: This analysis is problematic because the assumptions of OLS are violated when it is used with a non-interval outcome variable.

- ANOVA: If you use only one continuous predictor, you could “flip” the model around so that, say,

gpawas the outcome variable andapplywas the predictor variable. Then you could run a one-way ANOVA. This isn’t a bad thing to do if you only have one predictor variable (from the logistic model), and it is continuous. - Multinomial logistic regression: This is similar to doing ordered logistic regression, except that it is assumed that there is no order to the categories of the outcome variable (i.e., the categories are nominal). The downside of this approach is that the information contained in the ordering is lost.

- Ordered probit regression: This is very, very similar to running an ordered logistic regression. The main difference is in the interpretation of the coefficients.

Ordered logistic regression

Below we use the polr command from the MASS package to estimate an ordered logistic regression model. The command name comes from proportional odds logistic regression, highlighting the proportional odds assumption in our model. polr uses the standard formula interface in R for specifying a regression model with outcome followed by predictors. We also specify Hess=TRUE to have the model return the observed information matrix from optimization (called the Hessian) which is used to get standard errors.

Definitions

To understand how to interpret the coefficients, first let’s establish some notation and review the concepts involved in ordinal logistic regression. Let $Y$ be an ordinal outcome with $J$ categories. Then $P(Y \le j)$ is the cumulative probability of $Y$ less than or equal to a specific category $j = 1, \cdots, J-1$. The odds of being less than or equal a particular category can be defined as

$$\frac{P(Y \le j)}{P(Y>j)}$$

for $j=1,\cdots, J-1$ since $P(Y > J) = 0$ and dividing by zero is undefined. The log odds is also known as the logit, so that

$$log \frac{P(Y \le j)}{P(Y>j)} = logit (P(Y \le j)).$$

In R’s polr the ordinal logistic regression model is parameterized as

$$logit (P(Y \le j)) = \beta_{j0} – \eta_{1}x_1 – \cdots – \eta_{p} x_p.$$

Then we can fit the following ordinal logistic regression model:

## fit ordered logit model and store results 'm' m <- polr(apply ~ pared + public + gpa, data = dat, Hess=TRUE) ## view a summary of the model summary(m)

## Call: ## polr(formula = apply ~ pared + public + gpa, data = dat, Hess = TRUE) ## ## Coefficients: ## Value Std. Error t value ## pared 1.0477 0.266 3.942 ## public -0.0588 0.298 -0.197 ## gpa 0.6159 0.261 2.363 ## ## Intercepts: ## Value Std. Error t value ## unlikely|somewhat likely 2.204 0.780 2.827 ## somewhat likely|very likely 4.299 0.804 5.345 ## ## Residual Deviance: 717.02 ## AIC: 727.02

The estimated model can be written as:

$$ \begin{eqnarray} logit (\hat{P}(Y \le 1)) & = & 2.20 – 1.05*PARED – (-0.06)*PUBLIC – 0.616*GPA \\ logit (\hat{P}(Y \le 2)) & = & 4.30 – 1.05*PARED – (-0.06)*PUBLIC – 0.616*GPA \end{eqnarray} $$

In the output above, we see

- Call, this is

Rreminding us what type of model we ran, what options we specified, etc. - Next we see the usual regression output coefficient table including the value of each coefficient, standard errors, and t value, which is simply the ratio of the coefficient to its standard error. There is no significance test by default.

- Next we see the estimates for the two intercepts, which are sometimes called cutpoints. The intercepts indicate where the latent variable is cut to make the three groups that we observe in our data. Note that this latent variable is continuous. In general, these are not used in the interpretation of the results. The cutpoints are closely related to thresholds, which are reported by other statistical packages.

- Finally, we see the residual deviance, -2 * Log Likelihood of the model as well as the AIC. Both the deviance and AIC are useful for model comparison.

Some people are not satisfied without a p value. One way to calculate a p-value in this case is by comparing the t-value against the standard normal distribution, like a z test. Of course this is only true with infinite degrees of freedom, but is reasonably approximated by large samples, becoming increasingly biased as sample size decreases. This approach is used in other software packages such as Stata and is trivial to do. First we store the coefficient table, then calculate the p-values and combine back with the table.

## store table (ctable <- coef(summary(m)))

## Value Std. Error t value ## pared 1.04769 0.2658 3.9418 ## public -0.05879 0.2979 -0.1974 ## gpa 0.61594 0.2606 2.3632 ## unlikely|somewhat likely 2.20391 0.7795 2.8272 ## somewhat likely|very likely 4.29936 0.8043 5.3453

## calculate and store p values p <- pnorm(abs(ctable[, "t value"]), lower.tail = FALSE) * 2 ## combined table (ctable <- cbind(ctable, "p value" = p))

## Value Std. Error t value p value ## pared 1.04769 0.2658 3.9418 8.087e-05 ## public -0.05879 0.2979 -0.1974 8.435e-01 ## gpa 0.61594 0.2606 2.3632 1.812e-02 ## unlikely|somewhat likely 2.20391 0.7795 2.8272 4.696e-03 ## somewhat likely|very likely 4.29936 0.8043 5.3453 9.027e-08

We can also get confidence intervals for the parameter estimates. These can be obtained either by profiling the likelihood function or by using the standard errors and assuming a normal distribution. Note that profiled CIs are not symmetric (although they are usually close to symmetric). If the 95% CI does not cross 0, the parameter estimate is statistically significant.

(ci <- confint(m)) # default method gives profiled CIs

## 2.5 % 97.5 % ## pared 0.5282 1.5722 ## public -0.6522 0.5191 ## gpa 0.1076 1.1309

confint.default(m) # CIs assuming normality

## 2.5 % 97.5 % ## pared 0.5268 1.569 ## public -0.6426 0.525 ## gpa 0.1051 1.127

The CIs for both pared and gpa do not include 0; public does. The estimates in the output are given in units of ordered logits, or

ordered log odds. So for pared, we would say that for a one unit increase in pared (i.e., going from 0 to 1), we expect a 1.05 increase in

the expected value of apply on the log odds scale, given all of the other variables in the model are held constant. For gpa, we would say that for a one unit increase in gpa, we would expect a 0.62 increase in the expected value of apply in the log odds scale, given that all of the other variables in the model are held constant.

The coefficients from the model can be somewhat difficult to interpret because they are scaled in terms of logs. Another way to interpret logistic regression models is to convert the coefficients into odds ratios. To get the OR and confidence intervals, we just exponentiate the estimates and confidence intervals.

## odds ratios exp(coef(m))

## pared public gpa ## 2.8511 0.9429 1.8514

## OR and CI exp(cbind(OR = coef(m), ci))

## OR 2.5 % 97.5 % ## pared 2.8511 1.6958 4.817 ## public 0.9429 0.5209 1.681 ## gpa 1.8514 1.1136 3.098

These coefficients are called proportional odds ratios and we would interpret these pretty much as we would odds ratios from a binary logistic regression.

Interpreting the odds ratio

There are many equivalent interpretations of the odds ratio based on how the probability is defined and the direction of the odds. For a detailed justification, refer to How do I interpret the coefficients in an ordinal logistic regression in R? The (*) symbol below denotes the easiest interpretation among the choices.

Parental Education

- (*) For students whose parents did attend college, the odds of being more likely (i.e., very or somewhat likely versus unlikely) to apply is 2.85 times that of students whose parents did not go to college, holding constant all other variables.

- For students whose parents did not attend college, the odds of being less likely to apply (i.e., unlikely versus somewhat or very likely) is 2.85 times that of students whose parents did go to college, holding constant all other variables.

School Type

- For students in public school, the odds of being more likely (i.e., very or somewhat likely versus unlikely) to apply is 5.71% lower [i.e., (1 -0.943) x 100%] than private school students, holding constant all other variables.

- (*) For students in private school, the odds of being more likely to apply is 1.06 times [i.e., 1/0.943] that of public school students, holding constant all other variables (positive odds ratio).

- For students in private school, the odds of being less likely to apply (i.e., unlikely versus somewhat or very likely) is 5.71% lower than public school students, holding constant all other variables.

- For students in public school, the odds of being less likely to apply is 1.06 times that of private school students, holding constant all other variables (positive odds ratio).

GPA

- (*) For every one unit increase in student’s GPA the odds of being more likely to apply (very or somewhat likely versus unlikely) is multiplied 1.85 times (i.e., increases 85%), holding constant all other variables.

- For every one unit decrease in student’s GPA the odds of being less likely to apply (unlikely versus somewhat or very likely) is multiplied 1.85 times, holding constant all other variables.

Proportional odds assumption

One of the assumptions underlying ordinal logistic (and ordinal probit) regression is that the relationship between each pair of outcome groups is the same. In other words, ordinal logistic regression assumes that the coefficients that describe the relationship between, say, the lowest versus all higher categories of the response variable are the same as those that describe the relationship between the next lowest category and all higher categories, etc. This is called the proportional odds assumption or the parallel regression assumption. Because the relationship between all pairs of groups is the same, there is only one set of coefficients.

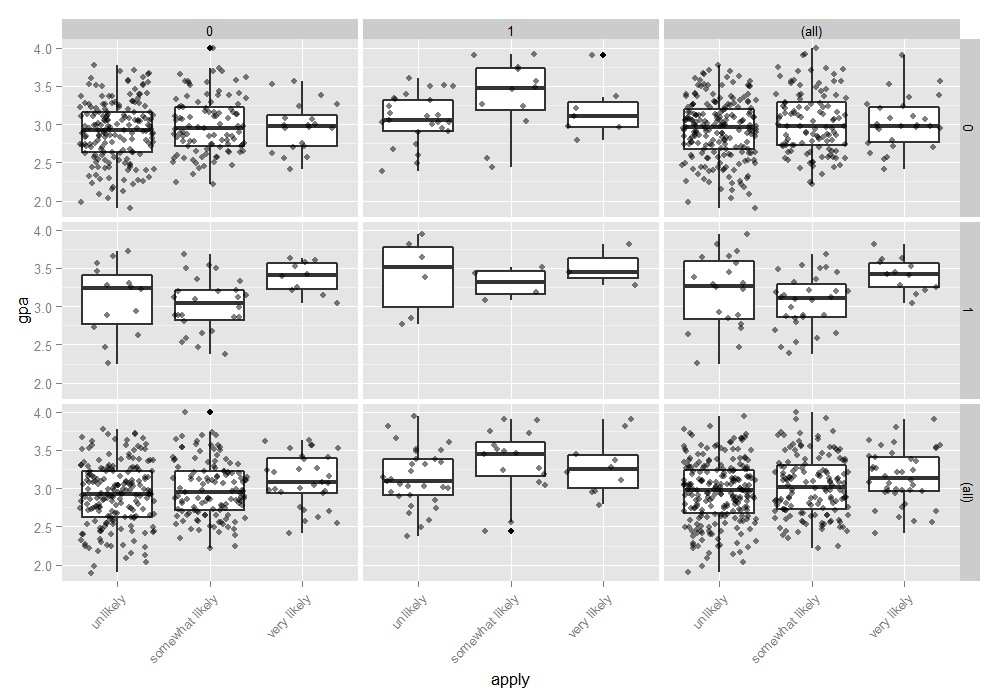

If this was not the case, we would need different sets of coefficients in the model to describe the relationship between each pair of outcome groups. Thus, in order to asses the appropriateness of our model, we need to evaluate whether the proportional odds assumption is tenable. Statistical tests to do this are available in some software packages. However, these tests have been criticized for having a tendency to reject the null hypothesis (that the sets of coefficients are the same), and hence, indicate that there the parallel slopes assumption does not hold, in cases where the assumption does hold (see Harrell 2001 p. 335). We were unable to locate a facility in R to perform any of the tests commonly used to test the parallel slopes assumption. However, Harrell does recommend a graphical method for assessing the parallel

slopes assumption. The values displayed in this graph are essentially (linear) predictions from a logit model, used to model the probability that y is greater than or equal to a given value (for each level of y), using one predictor (x) variable at a time. In order create this graph, you will need the Hmisc library.

The code below contains two commands (the first command falls on multiple lines) and is used to create this graph to test the proportional odds assumption. Basically, we will graph predicted logits from individual logistic regressions with a single predictor where the outcome groups are defined by either apply >= 2 and apply >= 3. If the difference between predicted logits for varying levels of a predictor, say pared, are the same whether the outcome is defined by apply >= 2 or apply >=3, then we can be confident that the proportional odds assumption holds. In other words, if the difference between logits for pared = 0 and pared = 1 is the same when the outcome is apply >= 2 as the difference when the outcome is apply >= 3, then the proportional odds assumption likely holds.

The first command creates the function that estimates the values that will be graphed. The first line of this command tells R that sf is a function, and that this function takes one argument, which we label y. The sf function will calculate the log odds of being greater than or equal to each value of the target variable. For our purposes, we would like the log odds of apply being greater than or equal to 2, and then greater than or equal to 3. Depending on the number of categories in your dependent variable, and the coding of your variables, you

may have to edit this function. Below the function is configured for a y variable with three levels, 1, 2, 3. If your dependent variable has 4 levels, labeled 1, 2, 3, 4 you would need to add 'Y>=4'=qlogis(mean(y >= 4)) (minus the quotation marks) inside the first set of parentheses. If your dependent variable were coded 0, 1, 2 instead of 1, 2, 3, you would need to edit the code, replacing each instance of 1 with 0, 2 with 1, and so on. Inside the sf function we find the qlogis function, which transforms a probability to a logit. So, we will basically feed probabilities of apply being greater than 2 or 3 to qlogis, and it will return the logit transformations of these probabilites. Inside the qlogis function we see that we want the log odds of the mean of y >= 2. When we supply a y argument, such as apply, to function sf, y >= 2 will evaluate to a 0/1 (FALSE/TRUE) vector, and taking the mean of that vector will give you the proportion of or probability that apply >= 2.

The second command below calls the function sf on several subsets of the data defined by the predictors. In this statement we see the summary function with a formula supplied as the first argument. When R sees a call to summary with a formula argument, it will calculate descriptive statistics for the variable on the left side of the formula by groups on the right side of the formula and will return the results in a nice table. By default, summary will calculate the mean of the left side variable. So, if we had used the code summary(as.numeric(apply) ~ pared + public + gpa) without the fun argument, we would get means on apply by pared, then by public, and finally by gpa broken up into 4 equal groups. However, we can override calculation of the mean by supplying our own function, namely sf to the fun= argument. The final command

asks R to return the contents to the object s, which is a table.

sf <- function(y) { c('Y>=1' = qlogis(mean(y >= 1)), 'Y>=2' = qlogis(mean(y >= 2)), 'Y>=3' = qlogis(mean(y >= 3))) } (s <- with(dat, summary(as.numeric(apply) ~ pared + public + gpa, fun=sf)))

## as.numeric(apply) N=400 ## ## +-------+-----------+---+----+--------+------+ ## | | |N |Y>=1|Y>=2 |Y>=3 | ## +-------+-----------+---+----+--------+------+ ## |pared |No |337|Inf |-0.37834|-2.441| ## | |Yes | 63|Inf | 0.76547|-1.347| ## +-------+-----------+---+----+--------+------+ ## |public |No |343|Inf |-0.20479|-2.345| ## | |Yes | 57|Inf |-0.17589|-1.548| ## +-------+-----------+---+----+--------+------+ ## |gpa |[1.90,2.73)|102|Inf |-0.39730|-2.773| ## | |[2.73,3.00)| 99|Inf |-0.26415|-2.303| ## | |[3.00,3.28)|100|Inf |-0.20067|-2.091| ## | |[3.28,4.00]| 99|Inf | 0.06062|-1.804| ## +-------+-----------+---+----+--------+------+ ## |Overall| |400|Inf |-0.20067|-2.197| ## +-------+-----------+---+----+--------+------+

The table above displays the (linear) predicted values we would get if we regressed our

dependent variable on our predictor variables one at a time, without the

parallel slopes assumption. We can evaluate the parallel slopes assumption by running

a series of binary logistic regressions with varying cutpoints on the dependent variable and checking the equality of coefficients across cutpoints. We thus relax the parallel slopes assumption to checks its tenability. To accomplish this, we transform the original, ordinal, dependent variable into a new, binary, dependent variable which is equal to zero if the original, ordinal dependent variable (here apply) is less than some value a, and 1 if the

ordinal variable is greater than or equal to a (note, this is what the ordinal

regression model coefficients represent as well). This is done for k-1 levels of

the ordinal variable and is executed by the as.numeric(apply) >= a coding below. The first line of code estimates the effect of pared on choosing “unlikely” applying versus “somewhat likely” or “very likely”. The second line of code estimates the effect of pared on choosing “unlikely” or “somewhat likely” applying versus “very likely” applying.

Looking at the intercept for this model (-0.3783), we see that it matches the

predicted value in the cell for pared equal to “no” in the column for Y>=1, the value below it, for

pared equals “yes” is equal to the intercept plus the coefficient for

pared (i.e. -0.3783 + 1.1438 = 0.765).

glm(I(as.numeric(apply) >= 2) ~ pared, family="binomial", data = dat)

## ## Call: glm(formula = I(as.numeric(apply) >= 2) ~ pared, family = "binomial", ## data = dat) ## ## Coefficients: ## (Intercept) pared ## -0.378 1.144 ## ## Degrees of Freedom: 399 Total (i.e. Null); 398 Residual ## Null Deviance: 551 ## Residual Deviance: 534 AIC: 538

glm(I(as.numeric(apply) >= 3) ~ pared, family="binomial", data = dat)

## ## Call: glm(formula = I(as.numeric(apply) >= 3) ~ pared, family = "binomial", ## data = dat) ## ## Coefficients: ## (Intercept) pared ## -2.44 1.09 ## ## Degrees of Freedom: 399 Total (i.e. Null); 398 Residual ## Null Deviance: 260 ## Residual Deviance: 252 AIC: 256

We can use the values in this table to help us assess whether

the proportional odds assumption is reasonable for our model. (Note,

the table is reproduced below, as well as above.) For example, when pared is

equal to “no” the difference between the predicted value for apply greater than or equal to

two and apply greater than or equal to three is roughly 2 (-0.378 – -2.440 = 2.062).

For pared equal to “yes” the difference in predicted values for apply greater

than or equal to two and apply greater than or equal to three is also roughly 2 (0.765 – -1.347 = 2.112).

This suggests that the parallel slopes assumption is reasonable (these differences are what graph below are plotting). Turning our attention to the predictions with public

as a predictor variable, we see that when public is set to “no” the difference in

predictions for apply greater than or equal to two, versus apply greater than or equal to

three is about 2.14 (-0.204 – -2.345 = 2.141). When public is set to “yes”

the difference between the coefficients is about 1.37 (-0.175 – -1.547 = 1.372). The

differences in the distance between the two sets of coefficients (2.14 vs. 1.37) may suggest

that the parallel slopes assumption does not hold for the predictor public. That

would indicate that the effect of attending a public versus private school is different for

the transition from “unlikely” to “somewhat likely” and “somewhat likely” to “very likely.”

The plot command below tells R that the object we wish to plot is s. The command

which=1:3 is a list of values indicating levels of y should be included in

the plot. If your dependent variable had more than three levels you would need

to change the 3 to the number of categories (e.g., 4 for a four category

variable, even if it is numbered 0, 1, 2, 3). The command pch=1:3 selects

the markers to use, and is optional, as are xlab='logit' which labels the

x-axis, and main=' ' which sets the main label for the graph to blank.

If the proportional odds assumption holds, for each predictor variable,

distance between the symbols for each set of categories of the dependent

variable, should remain similar. To help demonstrate this, we normalized all the first

set of coefficients to be zero so there is a common reference point. Looking

at the coefficients for the variable pared we see that the distance between the

two sets of coefficients is similar. In contrast, the distances

between the estimates for public are different (i.e., the markers are much

further apart on the second line than on the first), suggesting that the proportional

odds assumption may not hold.

s[, 4] <- s[, 4] - s[, 3] s[, 3] <- s[, 3] - s[, 3] s # print

## as.numeric(apply) N=400 ## ## +-------+-----------+---+----+----+------+ ## | | |N |Y>=1|Y>=2|Y>=3 | ## +-------+-----------+---+----+----+------+ ## |pared |No |337|Inf |0 |-2.062| ## | |Yes | 63|Inf |0 |-2.113| ## +-------+-----------+---+----+----+------+ ## |public |No |343|Inf |0 |-2.140| ## | |Yes | 57|Inf |0 |-1.372| ## +-------+-----------+---+----+----+------+ ## |gpa |[1.90,2.73)|102|Inf |0 |-2.375| ## | |[2.73,3.00)| 99|Inf |0 |-2.038| ## | |[3.00,3.28)|100|Inf |0 |-1.890| ## | |[3.28,4.00]| 99|Inf |0 |-1.864| ## +-------+-----------+---+----+----+------+ ## |Overall| |400|Inf |0 |-1.997| ## +-------+-----------+---+----+----+------+

plot(s, which=1:3, pch=1:3, xlab='logit', main=' ', xlim=range(s[,3:4]))

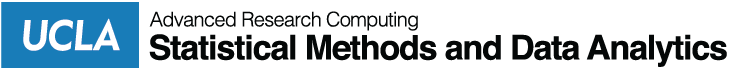

Once we are done assessing whether the assumptions of our model hold,

we can obtain predicted probabilities, which are usually easier to

understand than either the coefficients or the odds ratios. For example, we can vary

gpa for each level of pared and public and calculate

the probability of being in each category of apply. We do this by creating a new

dataset of all the values to use for prediction.

newdat <- data.frame( pared = rep(0:1, 200), public = rep(0:1, each = 200), gpa = rep(seq(from = 1.9, to = 4, length.out = 100), 4)) newdat <- cbind(newdat, predict(m, newdat, type = "probs")) ##show first few rows head(newdat)

## pared public gpa unlikely somewhat likely very likely ## 1 0 0 1.900 0.7376 0.2205 0.04192 ## 2 1 0 1.921 0.4932 0.3946 0.11221 ## 3 0 0 1.942 0.7325 0.2245 0.04299 ## 4 1 0 1.964 0.4867 0.3985 0.11484 ## 5 0 0 1.985 0.7274 0.2285 0.04407 ## 6 1 0 2.006 0.4802 0.4023 0.11753

Now we can reshape the data long with the reshape2 package and plot

all of the predicted probabilities for the different conditions. We plot the

predicted probilities, connected with a line, colored by level of the outcome,

apply, and facetted by level of pared and public. We also

use a custom label function, to add clearer labels showing what each column and row

of the plot represent.

lnewdat <- melt(newdat, id.vars = c("pared", "public", "gpa"), variable.name = "Level", value.name="Probability") ## view first few rows head(lnewdat)

## pared public gpa Level Probability ## 1 0 0 1.900 unlikely 0.7376 ## 2 1 0 1.921 unlikely 0.4932 ## 3 0 0 1.942 unlikely 0.7325 ## 4 1 0 1.964 unlikely 0.4867 ## 5 0 0 1.985 unlikely 0.7274 ## 6 1 0 2.006 unlikely 0.4802

ggplot(lnewdat, aes(x = gpa, y = Probability, colour = Level)) + geom_line() + facet_grid(pared ~ public, labeller="label_both")

Things to consider

- Perfect prediction: Perfect prediction means that one value of a predictor variable is associated with only one value of the response variable. If this happens, Stata will usually issue a note at the top of the output and will drop the cases so that the model can run.

- Sample size: Both ordered logistic and ordered probit, using maximum likelihood estimates, require sufficient sample size. How big is big is a topic of some debate, but they almost always require more cases than OLS regression.

- Empty cells or small cells: You should check for empty or small cells by doing a crosstab between categorical predictors and the outcome variable. If a cell has very few cases, the model may become unstable or it might not run at all.

- Pseudo-R-squared: There is no exact analog of the R-squared found in OLS. There are many versions of pseudo-R-squares. Please see Long and Freese 2005 for more details and explanations of various pseudo-R-squares.

- Diagnostics: Doing diagnostics for non-linear models is difficult, and ordered logit/probit models are even more difficult than binary models. For a discussion of model diagnostics for logistic regression, see Hosmer and Lemeshow (2000, Chapter 5). Note that diagnostics done for logistic regression are similar to those done for probit regression.

References

- Agresti, A. (1996) An Introduction to Categorical Data Analysis. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc

- Agresti, A. (2002) Categorical Data Analysis, Second Edition. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Harrell, F. E, (2001) Regression Modeling Strategies. New York: Springer-Verlag.

- Liao, T. F. (1994) Interpreting Probability Models: Logit, Probit, and Other Generalized Linear Models. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

- Powers, D. and Xie, Yu. Statistical Methods for Categorical Data Analysis. Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.