Robust regression is an alternative to least squares regression when data are contaminated with outliers or influential observations, and it can also be used for the purpose of detecting influential observations.

This page uses the following packages. Make sure that you can load

them before trying to run the examples on this page. If you do not have

a package installed, run: install.packages("packagename"), or

if you see the version is out of date, run: update.packages().

require(foreign) require(MASS)

Version info: Code for this page was tested in R version 3.1.1 (2014-07-10)

On: 2014-09-29

With: MASS 7.3-33; foreign 0.8-61; knitr 1.6; boot 1.3-11; ggplot2 1.0.0; dplyr 0.2; nlme 3.1-117

Please note: The purpose of this page is to show how to use various data analysis commands. It does not cover all aspects of the research process which researchers are expected to do. In particular, it does not cover data cleaning and checking, verification of assumptions, model diagnostics or potential follow-up analyses.

Introduction

Let’s begin our discussion on robust regression with some terms in linear regression.

Residual: The difference between the predicted value (based on the regression equation) and the actual, observed value.

Outlier: In linear regression, an outlier is an observation with large residual. In other words, it is an observation whose dependent-variable value is unusual given its value on the predictor variables. An outlier may indicate a sample peculiarity or may indicate a data entry error or other problem.

Leverage: An observation with an extreme value on a predictor variable is a point with high leverage. Leverage is a measure of how far an independent variable deviates from its mean. High leverage points can have a great amount of effect on the estimate of regression coefficients.

Influence: An observation is said to be influential if removing the observation substantially changes the estimate of the regression coefficients. Influence can be thought of as the product of leverage and outlierness.

Cook’s distance (or Cook’s D): A measure that combines the information of leverage and residual of the observation.

Robust regression can be used in any situation in which you would use least squares regression. When fitting a least squares regression, we might find some outliers or high leverage data points. We have decided that these data points are not data entry errors, neither they are from a different population than most of our data. So we have no compelling reason to exclude them from the analysis. Robust regression might be a good strategy since it is a compromise between excluding these points entirely from the analysis and including all the data points and treating all them equally in OLS regression. The idea of robust regression is to weigh the observations differently based on how well behaved these observations are. Roughly speaking, it is a form of weighted and reweighted least squares regression.

The rlm command in the MASS package command implements several versions of robust

regression. In this page, we will show M-estimation with Huber and bisquare

weighting. These two are very standard. M-estimation defines a weight function

such that the estimating equation becomes \(\sum_{i=1}^{n}w_{i}(y_{i} – x’b)x’_{i} = 0\).

But the weights depend on the residuals and the residuals on the weights. The equation is solved using Iteratively

Reweighted Least Squares (IRLS).

For example, the coefficient matrix at iteration j is

\(B_{j} = [X’W_{j-1}X]^{-1}X’W_{j-1}Y\)

where the subscripts indicate the matrix at a particular iteration (not rows or columns).

The process continues until it converges. In Huber weighting,

observations with small residuals get a weight of 1 and the larger the residual,

the smaller the weight. This is defined by the weight function

\begin{equation} w(e) = \left\{ \begin{array}{rl} 1 \quad \mbox{for} \quad |e| \leq k \\ \dfrac{k}{|e|} \quad \mbox{for} \quad |e| > k \\ \end{array} \right. \end{equation}

With bisquare weighting, all cases with a non-zero residual get down-weighted at least a little.

Description of the example data

For our data analysis below, we will use the crime dataset that appears in

Statistical Methods for Social Sciences, Third Edition

by Alan Agresti and Barbara Finlay (Prentice Hall, 1997). The variables are

state id (sid), state name (state), violent crimes per 100,000

people (crime), murders per 1,000,000 (murder), the percent of

the population living in metropolitan areas (pctmetro), the percent of

the population that is white (pctwhite), percent of population with a

high school education or above (pcths), percent of population living

under poverty line (poverty), and percent of population that are single

parents (single). It has 51 observations. We are going to use poverty

and single to predict crime.

cdata <- read.dta("https://stats.idre.ucla.edu/stat/data/crime.dta") summary(cdata)

## sid state crime murder ## Min. : 1.0 Length:51 Min. : 82 Min. : 1.60 ## 1st Qu.:13.5 Class :character 1st Qu.: 326 1st Qu.: 3.90 ## Median :26.0 Mode :character Median : 515 Median : 6.80 ## Mean :26.0 Mean : 613 Mean : 8.73 ## 3rd Qu.:38.5 3rd Qu.: 773 3rd Qu.:10.35 ## Max. :51.0 Max. :2922 Max. :78.50 ## pctmetro pctwhite pcths poverty ## Min. : 24.0 Min. :31.8 Min. :64.3 Min. : 8.0 ## 1st Qu.: 49.5 1st Qu.:79.3 1st Qu.:73.5 1st Qu.:10.7 ## Median : 69.8 Median :87.6 Median :76.7 Median :13.1 ## Mean : 67.4 Mean :84.1 Mean :76.2 Mean :14.3 ## 3rd Qu.: 84.0 3rd Qu.:92.6 3rd Qu.:80.1 3rd Qu.:17.4 ## Max. :100.0 Max. :98.5 Max. :86.6 Max. :26.4 ## single ## Min. : 8.4 ## 1st Qu.:10.1 ## Median :10.9 ## Mean :11.3 ## 3rd Qu.:12.1 ## Max. :22.1

Using robust regression analysis

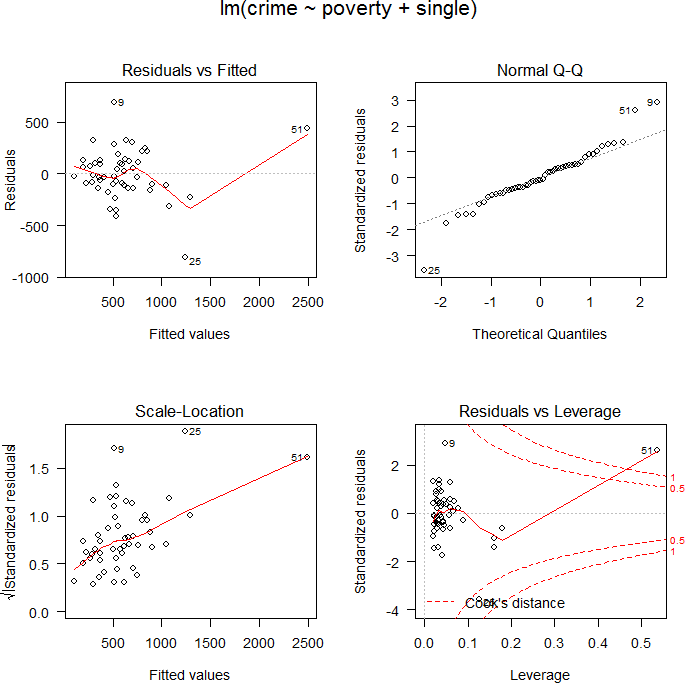

In most cases, we begin by running an OLS regression and doing some diagnostics. We will begin by running an OLS regression and looking at diagnostic plots examining residuals, fitted values, Cook’s distance, and leverage.

summary(ols <- lm(crime ~ poverty + single, data = cdata))

## ## Call: ## lm(formula = crime ~ poverty + single, data = cdata) ## ## Residuals: ## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max ## -811.1 -114.3 -22.4 121.9 689.8 ## ## Coefficients: ## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|) ## (Intercept) -1368.19 187.21 -7.31 2.5e-09 *** ## poverty 6.79 8.99 0.76 0.45 ## single 166.37 19.42 8.57 3.1e-11 *** ## --- ## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1 ## ## Residual standard error: 244 on 48 degrees of freedom ## Multiple R-squared: 0.707, Adjusted R-squared: 0.695 ## F-statistic: 58 on 2 and 48 DF, p-value: 1.58e-13

opar <- par(mfrow = c(2,2), oma = c(0, 0, 1.1, 0)) plot(ols, las = 1)

par(opar)

From these plots, we can identify observations 9, 25, and 51 as possibly problematic to our model. We can look at these observations to see which states they represent.

cdata[c(9, 25, 51), 1:2]

## sid state ## 9 9 fl ## 25 25 ms ## 51 51 dc

DC, Florida and Mississippi have either high leverage or large residuals. We can display the observations that have relatively large values of Cook’s D. A conventional cut-off point is \({4}/{n}\), where \(n\) is the number of observations in the data set. We will use this criterion to select the values to display.

d1 <- cooks.distance(ols) r <- stdres(ols) a <- cbind(cdata, d1, r) a[d1 > 4/51, ]

## sid state crime murder pctmetro pctwhite pcths poverty single d1 ## 1 1 ak 761 9.0 41.8 75.2 86.6 9.1 14.3 0.1255 ## 9 9 fl 1206 8.9 93.0 83.5 74.4 17.8 10.6 0.1426 ## 25 25 ms 434 13.5 30.7 63.3 64.3 24.7 14.7 0.6139 ## 51 51 dc 2922 78.5 100.0 31.8 73.1 26.4 22.1 2.6363 ## r ## 1 -1.397 ## 9 2.903 ## 25 -3.563 ## 51 2.616

We probably should drop DC to begin with since it is not even a state. We

include it in the analysis just to show that it has large Cook’s D and

demonstrate how it will be handled by rlm. Now we will look at

the residuals. We will

generate a new variable called absr1, which is the absolute value of the

residuals (because the sign of the residual doesn’t matter). We then print the

ten observations with the highest absolute residual values.

rabs <- abs(r) a <- cbind(cdata, d1, r, rabs) asorted <- a[order(-rabs), ] asorted[1:10, ]

## sid state crime murder pctmetro pctwhite pcths poverty single d1 ## 25 25 ms 434 13.5 30.7 63.3 64.3 24.7 14.7 0.61387 ## 9 9 fl 1206 8.9 93.0 83.5 74.4 17.8 10.6 0.14259 ## 51 51 dc 2922 78.5 100.0 31.8 73.1 26.4 22.1 2.63625 ## 46 46 vt 114 3.6 27.0 98.4 80.8 10.0 11.0 0.04272 ## 26 26 mt 178 3.0 24.0 92.6 81.0 14.9 10.8 0.01676 ## 21 21 me 126 1.6 35.7 98.5 78.8 10.7 10.6 0.02233 ## 1 1 ak 761 9.0 41.8 75.2 86.6 9.1 14.3 0.12548 ## 31 31 nj 627 5.3 100.0 80.8 76.7 10.9 9.6 0.02229 ## 14 14 il 960 11.4 84.0 81.0 76.2 13.6 11.5 0.01266 ## 20 20 md 998 12.7 92.8 68.9 78.4 9.7 12.0 0.03570 ## r rabs ## 25 -3.563 3.563 ## 9 2.903 2.903 ## 51 2.616 2.616 ## 46 -1.742 1.742 ## 26 -1.461 1.461 ## 21 -1.427 1.427 ## 1 -1.397 1.397 ## 31 1.354 1.354 ## 14 1.338 1.338 ## 20 1.287 1.287

Now let’s run our first robust regression. Robust regression is done by

iterated re-weighted least squares (IRLS). The command for running robust regression

is rlm in the MASS package. There are several weighting functions

that can be used for IRLS. We are

going to first use the Huber weights in this example. We will then look at

the final weights created by the IRLS process. This can be very

useful.

summary(rr.huber <- rlm(crime ~ poverty + single, data = cdata))

## ## Call: rlm(formula = crime ~ poverty + single, data = cdata) ## Residuals: ## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max ## -846.1 -125.8 -16.5 119.2 679.9 ## ## Coefficients: ## Value Std. Error t value ## (Intercept) -1423.037 167.590 -8.491 ## poverty 8.868 8.047 1.102 ## single 168.986 17.388 9.719 ## ## Residual standard error: 182 on 48 degrees of freedom

hweights <- data.frame(state = cdata$state, resid = rr.huber$resid, weight = rr.huber$w) hweights2 <- hweights[order(rr.huber$w), ] hweights2[1:15, ]

## state resid weight ## 25 ms -846.09 0.2890 ## 9 fl 679.94 0.3595 ## 46 vt -410.48 0.5956 ## 51 dc 376.34 0.6494 ## 26 mt -356.14 0.6865 ## 21 me -337.10 0.7252 ## 31 nj 331.12 0.7384 ## 14 il 319.10 0.7661 ## 1 ak -313.16 0.7807 ## 20 md 307.19 0.7958 ## 19 ma 291.21 0.8395 ## 18 la -266.96 0.9159 ## 2 al 105.40 1.0000 ## 3 ar 30.54 1.0000 ## 4 az -43.25 1.0000

We can see that roughly, as the absolute residual goes down, the weight goes up. In other words, cases with a large residuals tend to be down-weighted. This output shows us that the observation for Mississippi will be down-weighted the most. Florida will also be substantially down-weighted. All observations not shown above have a weight of 1. In OLS regression, all cases have a weight of 1. Hence, the more cases in the robust regression that have a weight close to one, the closer the results of the OLS and robust regressions.

Next, let’s run the same model, but using the bisquare weighting function. Again, we can look at the weights.

rr.bisquare <- rlm(crime ~ poverty + single, data=cdata, psi = psi.bisquare) summary(rr.bisquare)

## ## Call: rlm(formula = crime ~ poverty + single, data = cdata, psi = psi.bisquare) ## Residuals: ## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max ## -906 -141 -15 115 668 ## ## Coefficients: ## Value Std. Error t value ## (Intercept) -1535.334 164.506 -9.333 ## poverty 11.690 7.899 1.480 ## single 175.930 17.068 10.308 ## ## Residual standard error: 202 on 48 degrees of freedom

biweights <- data.frame(state = cdata$state, resid = rr.bisquare$resid, weight = rr.bisquare$w) biweights2 <- biweights[order(rr.bisquare$w), ] biweights2[1:15, ]

## state resid weight ## 25 ms -905.6 0.007653 ## 9 fl 668.4 0.252871 ## 46 vt -402.8 0.671495 ## 26 mt -360.9 0.731137 ## 31 nj 346.0 0.751348 ## 18 la -332.7 0.768938 ## 21 me -328.6 0.774103 ## 1 ak -325.9 0.777662 ## 14 il 313.1 0.793659 ## 20 md 308.8 0.799066 ## 19 ma 297.6 0.812597 ## 51 dc 260.6 0.854442 ## 50 wy -234.2 0.881661 ## 5 ca 201.4 0.911714 ## 10 ga -186.6 0.924033

We can see that the weight given to Mississippi is dramatically lower using the bisquare weighting function than the Huber weighting function and the parameter estimates from these two different weighting methods differ. When comparing the results of a regular OLS regression and a robust regression, if the results are very different, you will most likely want to use the results from the robust regression. Large differences suggest that the model parameters are being highly influenced by outliers. Different functions have advantages and drawbacks. Huber weights can have difficulties with severe outliers, and bisquare weights can have difficulties converging or may yield multiple solutions.

As you can see, the results from the two analyses are fairly different,

especially with respect to the coefficients of single and the constant

(intercept).

While normally we are not interested in the constant, if you had centered one or

both of the predictor variables, the constant would be useful. On the

other hand, you will notice that poverty is not statistically significant

in either analysis, whereas single is significant in both analyses.

Things to consider

- Robust regression does not address issues of heterogeneity of variance.

This problem can be addressed by using functions in the

sandwichpackage after thelmfunction. - The examples shown here have presented

Rcode for M estimation. There are other estimation options available inrlmand other R commands and packages: Least trimmed squares usingltsRegin therobustbasepackage and MM usingrlm.

References

- Li, G. 1985. Robust regression. In Exploring Data Tables, Trends, and Shapes, ed. D. C. Hoaglin, F. Mosteller, and J. W. Tukey, Wiley.

- John Fox, Applied regression analysis, linear models, and related models, Sage publications, Inc, 1997